With the Austin summer coming in hot � literally � the cool waters of Lady Bird Lake in the scenic center of downtown look inviting to locals and tourists alike. But despite the many kayakers out on the water, you won't find many swimmers beneath the surface.

In 1964, after the drowning of two young sisters, the city of Austin banned swimming in Lady Bird Lake, then Town Lake. Today, it stands as a Class C misdemeanor, like public intoxication, often to the dismay and confusion of Austinites.

Many people question why the old, reactionary ban is still in effect and wonder what it would take to make the Austin hot spot swimmable.

“From the meetings I've attended, at least two of the council members were kind of getting pressure to open up swimming or give some concrete answers of why swimming is not open in the lake,� said Lt. Elijah Myrick, who leads Austin's lake patrol unit, a team of six police officers.

In short, Myrick said it would take a coordinated effort from multiple organizations before the city repealed its ban on any portion of the lake.

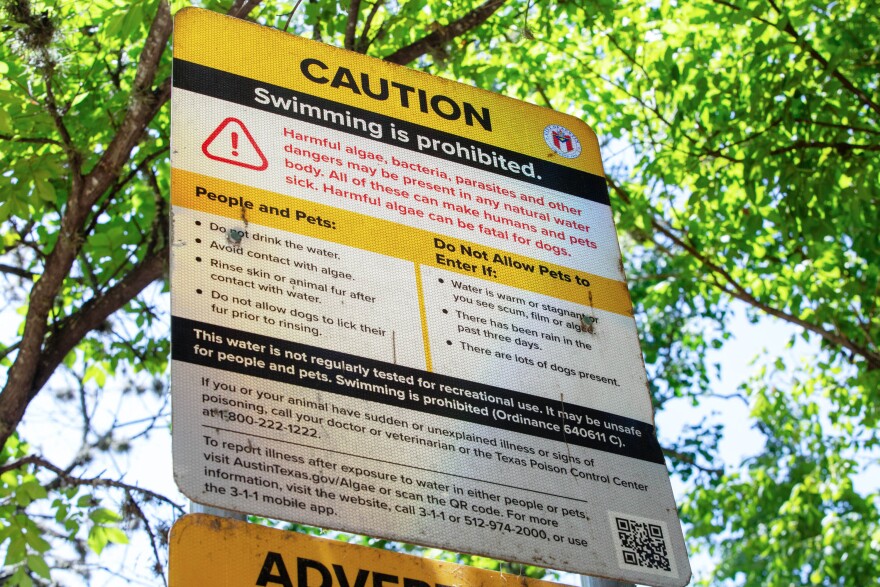

Experts and the public alike have theorized about the reasons swimming is not allowed: strong currents, dangerous debris and, more recently, the presence of blue-green algae.

Water quality is also a factor to consider now, Andrew Clamann, manager of applied watershed science with Watershed Protection, said. It played no role in the initial ban, he said, noting the Clean Water Act didn't go into effect until 1972.

“All these rules that we've come up with to protect our creeks have kind of applied to development that happened after the '80s and '90s," Clamann said. "That urban core developed so long ago that we don't have those protections.�

Those protections include planting vegetated buffers to prevent rainwater from washing stuff from the urban environment � like oils, pesticides, waste and everything else found on roads, lawns and Austin properties � into the lake, especially during rain and flooding events, Clamann said. Ingesting those toxins through your ears, nose or mouth could be dangerous, he said.

“I’m not a biologist,� Myrick said. “I can just tell you, we dive in it, and I’ve already had two ear infections this year, so there is definitely a water quality issue.�

It’s what Myrick sees underwater during dive training that concerns him the most, though: debris � not only loads of e-scooters, but also larger construction materials.

And there are also the drop-offs.

“Urban waterways are very deceptive,� he said. “You can be standing at 2 or 3 foot, and then you're in 17 foot, and, you know, most people, they're not ready for that level.�

He also noted the lake’s proximity to Austin’s entertainment district, increasing the likelihood of swimmers being intoxicated.

Myrick quickly dismissed rumors of serial killers, saying APD could do a better job of following up with the causes of death after bodies are found in the lake.

“I've been a part of a lot of these recoveries,� he said. “And I can tell you, there's been nothing truly nefarious going on in the lake.�

Both Clamann and Myrick agree the first step to making Lady Bird Lake swimmable is choosing a portion of the nearly 6-mile lake to prepare and monitor.

Clamann said the water quality would be better upstream of the urban core. Downstream locations also receive pollutants from the Highland Lakes up the river, he said.

“We wouldn't be able to remove it or clean it or make it appropriate," he said. "We would just be able to monitor it.�

Clamann said the Watershed Department's role, if the ban were to be lifted, would be to continue to monitor the water regularly, working with Austin Public Health to assess the dangers of E.coli concentration levels that fluctuate with increased flows or rainfall.

Increased flows, either from streams or releases from the Tom Miller Dam, can make swimming more dangerous. Myrick pointed to two paddleboard deaths this year because the individuals removed their life jackets and weren't strong swimmers.

Lucas Massie, the assistant director of the Parks and Recreation Department, which partially oversees Barton Springs Pool, noted other factors to consider as well: proximity to parking areas and amenities, the ability to dredge the lake after severe flooding and the need for trained lifeguards and potentially EMS personnel.

“If someone's in distress, swimming in 14 foot of water with very limited visibility, it's just a drastically different operation than, you know, your 17-year-old lifeguard at your neighborhood swimming pool,� Myrick said.

CapTex Tri, an annual Austin triathlon, is one of � if not the only � event that permits swimming in Lady Bird Lake. Race coordinators from Supertri, which manages the race, submit a safety plan to the city every year. Scott Nelson, Supertri's general manager, said that includes information about water-quality testing, lifeguards, lake patrol and a custom dock for entry and exit.

Other Austin water holes permit swimming, but many continue to tout Lady Bird Lake’s beauty and central location. Since the minimally staffed lake patrol unit is often busy maintaining boat safety on Lake Austin, Myrick said, people already swim illegally in Lady Bird Lake. If it were allowed, he guessed there wouldn’t be a huge increase in the number of people swimming.

But with any increase would come an increase in deaths.

“It's not to say that we shouldn't open up swimming,� Myrick said. “Riding your bike in Austin is not necessarily a safe thing to do, but I mean, the government, we don't prohibit doing it. We just set a lot of rules around it.�